NeurIPS2020

Program Synthesis

Discussion

- Constraint of program syntax: ****All of these methods provide the syntax of programs as an inductive bias. A fixed syntax obviously constrains the space of concepts that can be learned. In order to increase the flexibility of learnable concepts, two questions to ask are:

- Is there a program syntax that can encapsulate the space of all possible rules? (a Turing complete program syntax). Even if such a thing existed, search complexity on it would be intractable.

- Can program learning be meta learned? By learning a few programs from given data, can you become better at learning programs from another of data set i.e. that follow different grammar? None of the papers test this.

- Online learning: Model proposed in [9] needs to be trained offline and applied during user interaction. To make interaction easier, it would help if the model could adapt to the user during interaction i.e. learn online.

- Analogues: Symbolic vs neural representations is analogous to System 2 vs System 1 thinking in that the former is interpretable while the latter is not. Also, a major question is regarding the origin of discrete 'concepts'. Neurosymbolic models like [1] provide the program representation as an inductive bias. But in neuroscience, it seems as though instead of discreteness being hardcoded into the architecture, it emerges from neural representations. Similar to original Meta RL paper where meta learning emerges in RNNs learning to perform tasks.

Datasets

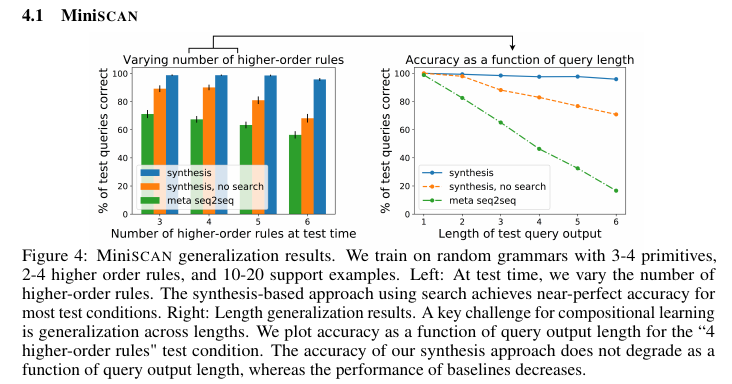

- MiniSCAN [5]: The goal of this domain is to learn compositional, language-like rules from a very limited number of examples.

- SCAN [4]: Consists of synthetic language command paired with discrete action sequence. The goal of SCAN is to test the compositional abilities of neural networks when test data varies systematically from training data

Papers

1. Learning Compositional Rules via Neural Program Synthesis

Authors: Nye, Solar-Lezama, Tenenbaum, Lake. NeurIPS 2020.

- Task: Few shot compositional rule learning from training data (support inputs) consisting of query-result pairs.

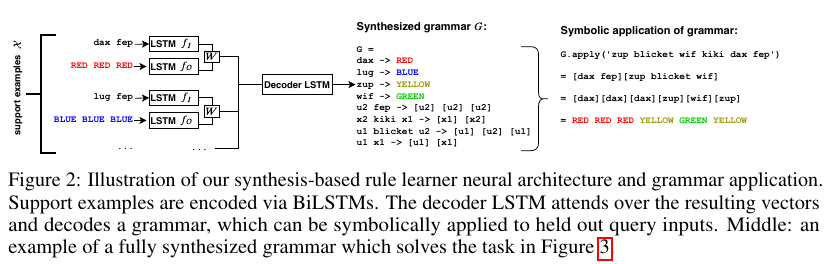

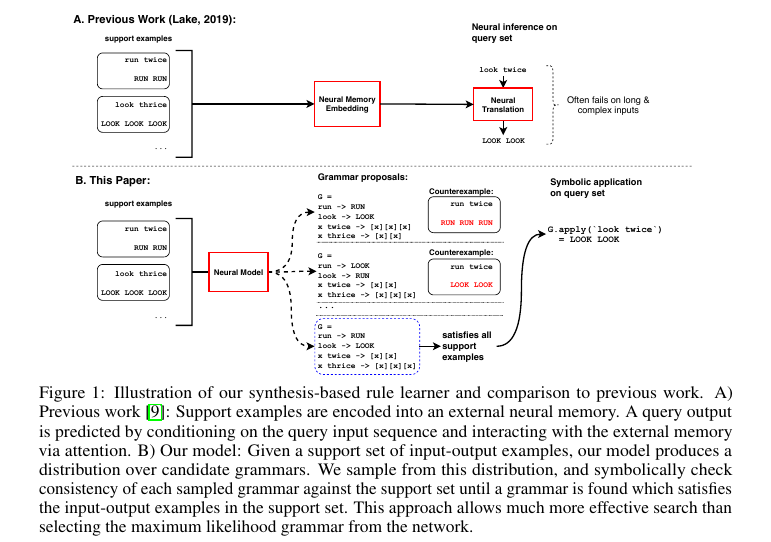

- Method: Generates an explicitly symbolic 'grammar' program using a neural encoder-decoder pair which is run on unseen query inputs to yield results.

- Training: Each episode consists of a single grammar being sampled from the grammar distribution. Compatible support set of 10-20 examples are generated. Using supervised learning, the model is trained to generate the grammar given support examples. Even [2] follows the same training procedure with one difference: since it doesn't use grammars, its trained on a seq2seq problem of generating support output given input.

- Testing: Grammar is sampled from learned synthesis model. A search process involves checking how well the grammar satisfies support examples. This runs until either a grammar satisfies all of them or search budget runs out in which case, grammar which satisfied most no. of examples is chosen. Unlike seq2seq model which is forced to operate with network learned from training process (i.e. it gets only 1 try), this model can guess-and-check until it gets everything right.

- Model architecture: 1 BiLSTM each for support input and output, followed by hidden layer which combines them to form a single vector representation ($h_i$) for a support example. LSTM decoder outputs sequence token by token while attending to the support input hidden states ($h_i$) via attention. Note that attention is done between support examples which ensures that this approach can focus on relevant examples at each decoding step (unlike RobustFill [3] which uses separate encoder decoders for each example). Output tokens are parsed into grammar.

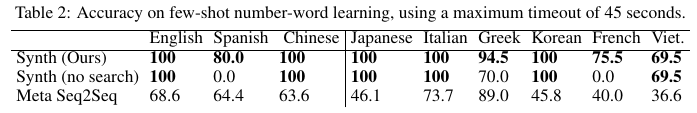

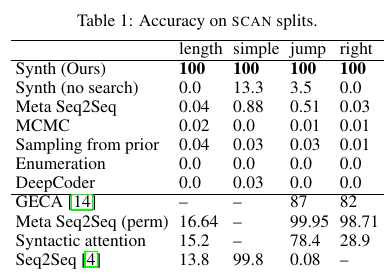

- Results:

- Also, expected to be more robust (due to checking mechanism) and interpretable (due to explicit symbolic grammar) than neural models.

2. Program Synthesis with Pragmatic Communication

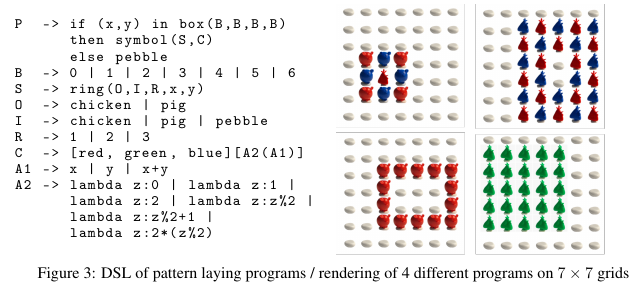

Authors: Pu, Ellis, Kryven, Tenenbaum, Solar-Lezama. NeurIPS 2020.

- Task: Program synthesis is the task of learning a program that generates a given specification. Example: For the spec Richard Feynman → Mr. Feynman, a program would be

Mr. + last_word(input). But its easy for the given spec to under-specify the intent. Example: The synthesizer might learn to just always print Mr. Feynman if just given the above example. To prevent this, previous methods use inductive biases. Example: FlashFill [6] penalises constant strings. [7] uses handcrafted features to make up for failures of [6].

-

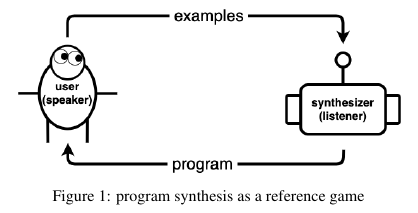

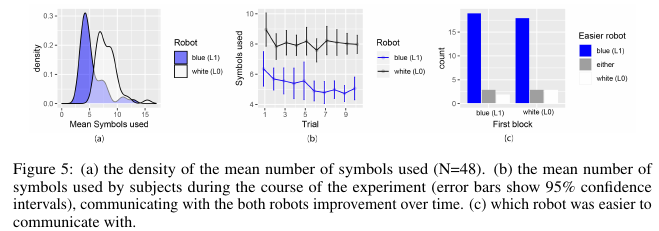

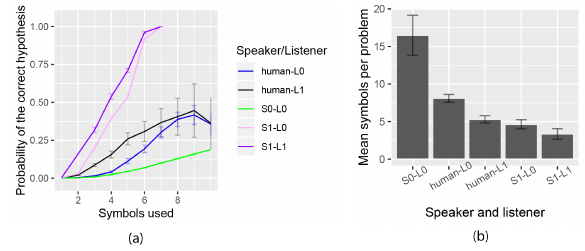

Formulation as a reference game: User communicates a concept $h$ (program) using utterances $u_i$ (examples). Synthesizer $S$'s job is to obtain the concept from these utterances. So communication is successful if $h = L(S(h))$ and efficient if the set of utterances is small. Usually, to build in human speaking convention into the model, other approaches use human annotated datasets. But here, the integrating pragmatic communication into the synthesizer enables it to learn without it.

-

See paper for proof that resulting convention from speaker listener pair is both efficient and human usable. RL approaches involving communication between agents [8] are good but not human usable.

-

Method:

- Literal Listener $L_0$: Upon receiving a set of examples $D$, $L_0$ samples uniformly from the set of consistent concepts.

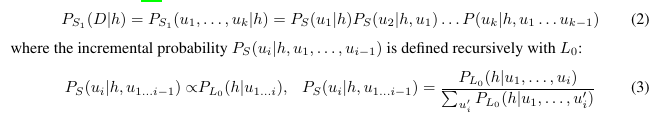

- Pragmatic Speaker $S_1$: Models the speakers generation of examples sequentially.

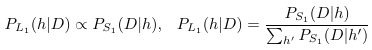

- Informative Listener $L_1$: Reasons about $S_1$.

This above process is very inefficient. So they propose a more efficient procedure (see paper) using version space algebra and memoization (like DP?). But even after this, its much more inefficient than SOTA program synthesizers.

-

Experiments: Task is to place some shapes with certain colours on a grid. Space of programs is 17976. Atomic examples are of the form $((x,y),s))$ where first element is coordinates and second is symbol. 343 atomic examples. Human studies were carried out.

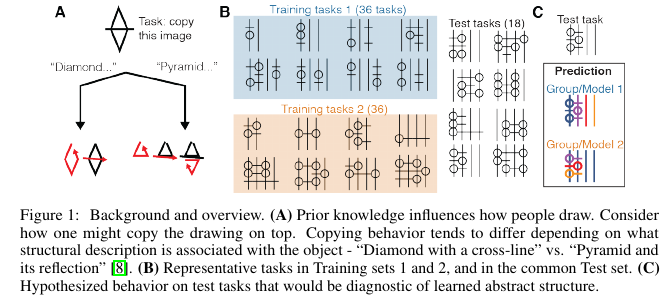

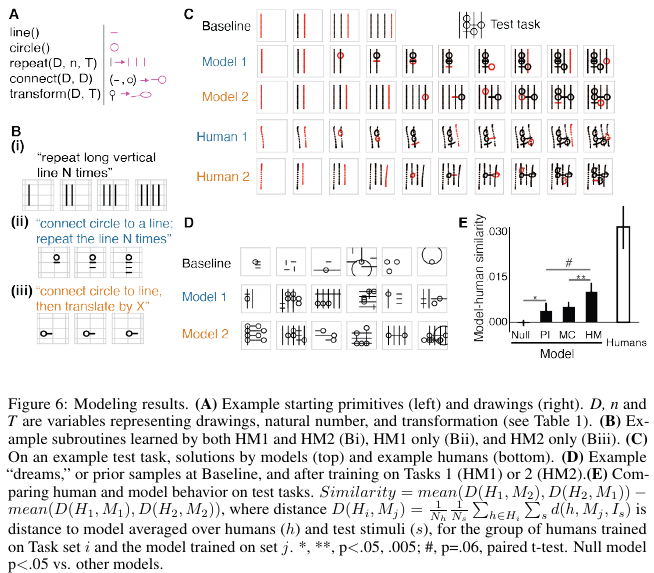

3. Learning abstract structure for drawing by efficient motor program induction

Authors: Tian, Ellis, Kryven, Tenenbaum. NeurIPS 2020.

- Task: To a) understand how humans infer structure from examples, b) develop a program learning based model of this and compare with human subjects on a novel task. Proposes a novel, ambiguous copying task. Model they've developed aims to be abstract and compositional.

- Method:

- Results:

References

- Nye, Maxwell I., Armando Solar-Lezama, Joshua B. Tenenbaum, and Brenden M. Lake. "Learning Compositional Rules via Neural Program Synthesis." arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.05562 (2020).

- Brenden M Lake. Compositional generalization through meta sequence-to-sequence learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 9788–9798, 2019.

- Amit Zohar and Lior Wolf. Automatic program synthesis of long programs with a learned garbage collector. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 2094–2103,

- Brenden Lake and Marco Baroni. Generalization without systematicity: On the compositional skills of sequence-to-sequence recurrent networks. In 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018, pages 4487–4499. International Machine Learning Society (IMLS), 2018.

- Brenden M Lake, Tal Linzen, and Marco Baroni. Human few-shot learning of compositional instructions. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2019.

- Oleksandr Polozov and Sumit Gulwani. Flashmeta: A framework for inductive program synthesis. ACM SIGPLAN Notices, 50(10):107–126, 2015.

- Kevin Ellis and Sumit Gulwani. Learning to learn programs from examples: Going beyond program structure. IJCAI, 2017.

- Mike Lewis, Denis Yarats, Yann N Dauphin, Devi Parikh, and Dhruv Batra. Deal or no deal? end-to-end learning for negotiation dialogues. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05125, 2017.

- Pu, Yewen, Kevin Ellis, Marta Kryven, Joshua B Tenenbaum, and Armando Solar-Lezama. “Program Synthesis with Pragmatic Communication,” n.d., 11.

- Tian, Lucas Y, Kevin Ellis, Marta Kryven, and Joshua B Tenenbaum. “Learning Abstract Structure for Drawing by Efficient Motor Program Induction,” n.d., 12.